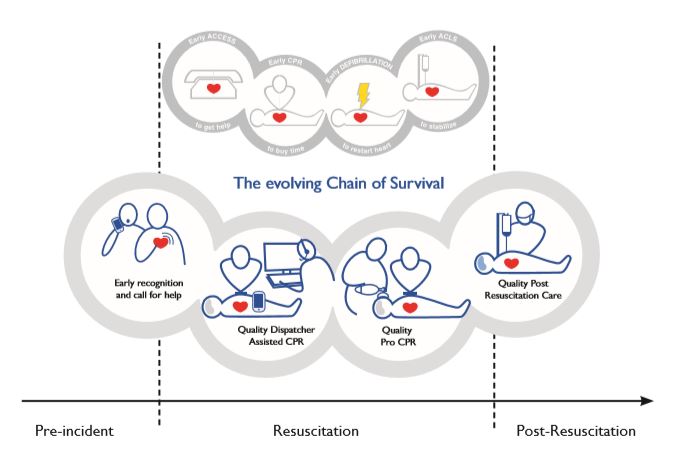

Sudden cardiac arrest in the community is still a major cause of death despite significant advances in prevention and therapy over the last 60 years. The visual metaphor for treatment of such cardiac arrests has evolved through advances in medical and educational science into what is called the Chain of Survival. Each circle represents one step in the chain from the bystander’s recognition of the emergency; calling for help and being coached by the dispatcher in applying CPR; high performance CPR and early defibrillation by first responders or Emergency Medical Technicians; further therapy and stabilisation by paramedics; and finally hospital care.

Improving survival in the community

Another version of the Chain of Survival includes a circle before bystander intervention: early prevention. And measures such as exercise, diet, and drug therapy to control cholesterol and blood pressure have been very effective in reducing cardiovascular disease in high-income countries (HICs).

The Global Potential

Although the emphasis until the last decade was on HICs, cardiac arrest is not only a problem in such societies.

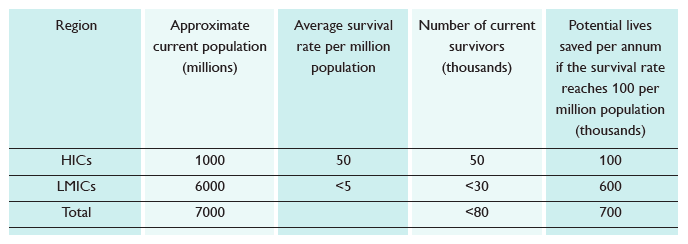

In fact, 86% of all global cardiac arrests are estimated to occur in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) where survival rates are lowest and the opportunity for impact is greatest. Numerous studies show that survival in HICs averages about 50 per million population with the highest performing centres exceeding 100 per million population. The survival data for LMICs is poor but the current average survival rate is believed to be well under 5 per million population. The table shows the potential for lives to be saved if everyone approached the performance of the best: a total of more than 600,000 extra lives per annum.

The shared 2030 goal is to help save 150,000 extra lives from cardiac arrest every year. About 50,000 will be the lives of in-hospital patients, but the lion’s share will be about 100,000 in the community: representing about 1/6th of the global potential. Based on recent data approximately 60% (i.e. 60,000) of this potential is likely to come from the first two links, 25% from the early responder link, and the balance from professional care.

| Region | Approximate current population (millions) | Average survival rate per million population | Number of current survivors (thousands) | Potential lives saved per annum if the survival rate reaches 100 per million population (thousands) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HICs | 1000 | 50 | 50 | 100 |

| LMICs | 6000 | <5 | <30 | 600 |

| Total | 7000 | <80 | 700 |

Shelisha and Khalif’s Story

The family had gathered for a barbecue at their London home in the UK. Shelisha was upstairs with her son, Shylio, when she heard a bloodcurdling scream and ran downstairs. Outside, her sister, brother and dad had found her nephew, Khalif, in the pond and pulled him out. The two-year old was lifeless. Having been trained in CPR at work, Shelisha immediately began chest compressions and rescue breathing.

“I was very calm, almost robotic; I knew I had to continue without stopping,” she said later. When the ambulance arrived after 15 minutes and the paramedics took over, they told the family that there was a faint heartbeat – but Khalif was still unconscious. Rushed to hospital, he was transferred to intensive care where he made a full recovery.

Alone at home when her husband collapses – and yet, thanks to the dispatcher, part of an instant team.

Mobilising the First Responding Team

Over 70% of all witnessed community cardiac arrests occur in the home where there is most likely only one rescuer. But the rescuer is never alone if a telephone is near to hand – mobile phones are now ubiquitous – and professional help is given over the phone by the ambulance dispatcher to help recognise the cardiac emergency and guide the rescuer in performing CPR until a volunteer first responder or ambulance arrives. Such “telephone CPR” (T-CPR) can be very effective especially when the bystander has previously received some community CPR training including simulating interaction with the ambulance dispatcher.

Looking forward, the challenges and opportunities are on two fronts: increasing the number of people who receive community training in CPR and improving the quality and efficiency of such training; and maximising the interaction between the rescuer and the dispatcher to improve the quality of the CPR delivered to the casualty. Digital advances in training products and methodologies and the widespread use of mobile phones will open new opportunities for success. For example:

- enabling the dispatcher to monitor the rescuer’s performance and give feedback where needed;

- video assistance of the caller by the dispatcher – now in use in Denmark, Korea and Japan;

- use of Artificial Intelligence to assist the dispatcher – as video and audio data from the contact between rescuer and dispatcher becomes available, machine learning will be used to improve early recognition of the character of the emergency which is critical not only in cardiac arrest but also in cases of stroke and sepsis.

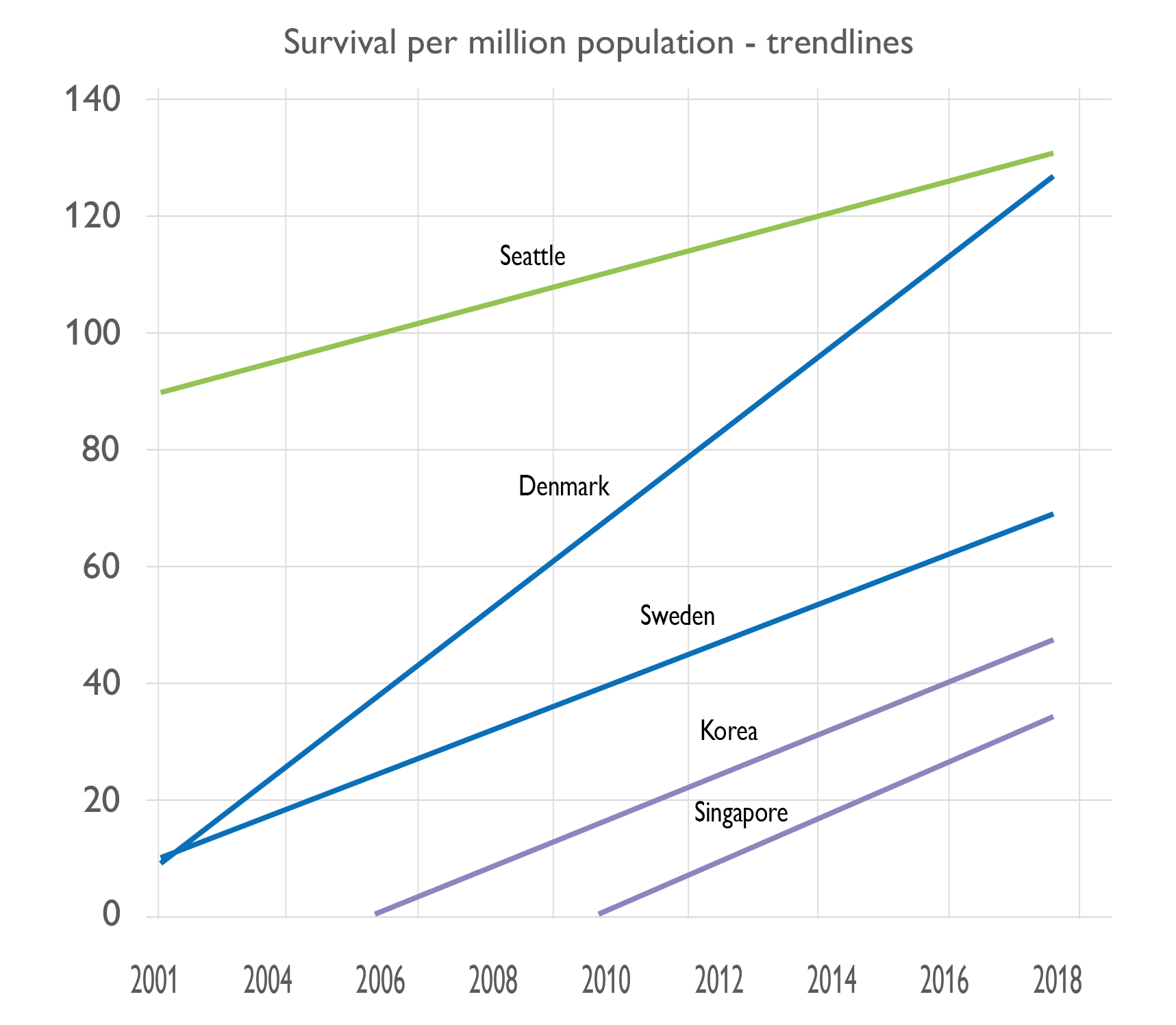

Such a so-called first resuscitation team of bystander and dispatcher has been the key to recent success in Korea. It was in 2013 that Laerdal helped with dispatcher training in Seoul and the following year partnered with Seoul National University Hospital and Seoul Metropolitan Government to develop a complementary CPR training program. Called HEROS it prepared the bystander for interacting with the dispatcher. In the subsequent four years, survival rates increased by 50% from 29 per million population in 2014 to 44 per million in 2018.

Four-Fold Increase in Survival in Denmark

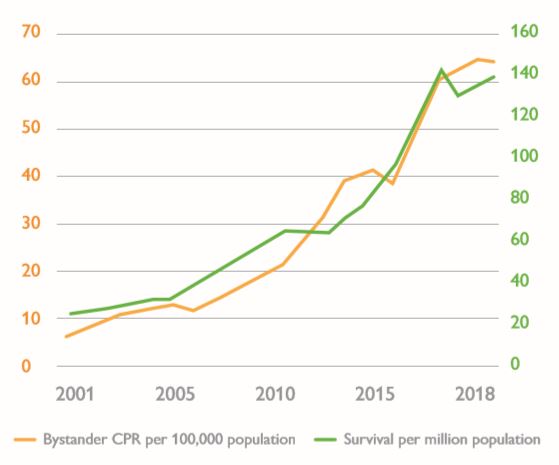

The Danish Cardiac Arrest Register was established in 2001 and it showed that only 4% of those that had a cardiac arrest in the community survived beyond 30 days of their arrest, just over 30 per million population. Recent results show that survival has increased four-fold to 16% – 140 per million population – now on a par with the best in the world, Seattle, USA.

This has been achieved following the principles that were the basis of the Seattle success and were embodied in the ten steps subsequently adopted by the Global Resuscitation Alliance.

Key actions included:

- Dispatcher assistance to the bystander.

- First aid training during driving lessons. This has been compulsory since 2006.

- First aid training in schools. This is also obligatory. And since 2006, the TrygFoundation has been distributing manikin sets to schools free of charge and free training material has been available from the Danish Resuscitation Council.

- Registration of volunteer first aiders willing and available to assist with CPR (and collect a defibrillator) if they are near a cardiac arrest incident.They receive an alarm from the dispatcher on their mobile phone directing them to the incident and identifying where the nearest defibrillator is located.These actions have all contributed to an increase in bystander CPR from about 1 in 4 cases of sudden cardiac arrest in 2001 to 4 out of 5 cases in 2018.The graph shows how this increase correlates very closely with the increase in survival over that period.

Freddy Lippert

Director of Copenhagen EMS Services

Gamified QCPR race with Bluetooth communication.

Improving Community CPR Training

Good data are scarce on the number of new CPR trainees added to the global pool each year; many include those who have been trained before and are having their skills refreshed. However, the number is probably about 10 million per annum in HICs. The next question to answer is: what does this need to increase by to achieve the shared goal? The best guess is that it would need to be about 10 times the current figure.

Based on data from Sweden and Denmark, it has been estimated that best-practice CPR coverage is achieved when 60% of the target population age 18-80 years are trained and are supported with T-CPR. This would equate globally to having a pool of about 3 billion trainees for maximum effect. To reach the shared goal of 60,000 extra lives saved in the first two links of the Chain of Survival (1/6th of the global potential) mentioned earlier would therefore equate to a pool of about 500 million new rescuers. That means an average of an additional 50 million trainees per annum over the next ten years, reaching a peak of about 100 million per annum.

Such a large increase in such a relatively short time will require a radical change in training methodology and delivery, which is more likely to happen in societies which are not wedded to current methods. And these new trainees will need to be concentrated in societies that are developing the other links in the Chain of Survival to achieve a high survival rate. These factors point to Asia as being a prime target, given initiatives such as HEROS, PAROS – the Pan-Asian Resuscitation Outcomes Study, the formation of the Asian Association for EMS, and the activities of the Global Resuscitation Alliance in that continent. That does not, however, decry the need for initiatives in well-developed systems. For example, a nationwide program for training school children has contributed, along with first responder defibrillation initiatives, to a remarkable increase in survival in Denmark over the last 10 years. And the British Heart Foundation’s Nation of Lifesavers program, started in the UK in 2014, has trained 5 million new lifesavers and reached 90% of UK secondary schools.

Current initiatives that can help increase the number of volunteers trained and improve CPR competence include:

- A complete classroom solution – using video-based instruction, data-driven real-time feedback, a cognitive quiz on smartphones and a gamified QCPR race to stimulate competition and quality improvement. There is also a data dashboard which helps such improvement: if a student struggles with a parameter, for example ventilation volume, the video and hands-on training are adjusted to help correct this.

- With Bluetooth communication from each trainee’s manikin to a tablet, one course facilitator can monitor and give feedback on the performance of up to 42 students. This is about 6 times the traditional facilitator:student ratio, and initial positive experience with such a system in Japan has resulted in a request on the possibility of increasing this ratio even further. It has been validated in Beijing and Shanghai and is being rolled out in China as an integral part of the WeCan CPR training program.

- Greater inclusion of defibrillator training in CPR programs – to maximise the usage of Public Access Defibrillators (see next section) by the lay public. An example is the program in Shenzhen, China where the law requires 100 laypersons to be trained for each defibrillator installed in a public place.

- Future initiatives could include more digitally-oriented home training solutions for those who typically do not go to CPR classes, including even simpler simulators than the innovative Mini Anne combined with online videos and VR simulations on smartphones. Improved school CPR training programs including e-learning and student instructors could also be beneficial.

The Restart a Heart Day has grown from a European initiative to a world event.

On or around Oct 16 every year, citizens of all countries are mobilised to Learn CPR, often with “Kids save lives” as a common theme. Participation has been growing year by year, reaching over 1 million in 2019.

Mr. Ha’s Story

Having finished the marathon track of a triathlon event in Seoul, South Korea, Mr. Ha (53), suddenly collapsed.

The emergency team from Hallym University Hospital arrived within 3 minutes. After 1 minute of CPR and a single AED shock, his heart resumed beating. He was still unconscious, but high quality hospital care had him fully recovered after a few hours.

A professional runner for many years, Mr. Ha had attended several CPR courses, and is able to appreciate fully the importance of an effective Chain of Survival. Having resumed running, he is now an enthusiastic CPR supporter on every marathon and all IronMan games.

Activating a Community of Life Savers

In addition to early CPR, the intervention shown to have a significant effect on survival from community cardiac arrest is early defibrillation. This has resulted in the placement over the last 20 years or so of a very large number, in excess of 5 million by industry estimates, of Automatic External Defibrillators (AEDs) in public places – so called Public Access Defibrillators. However, these defibrillators have been used on very few occasions considering the number in place – by some estimates in less than 1% of cardiac arrests. A literature review by researchers from Warwick University (UK) and the London Ambulance Service published in 2017 identified several barriers to their use including few people knowing what an AED is, where to find one, or how and by whom one can be used. Even amongst those who might find one and know how to use it, lack of confidence and fear of harm are common barriers to actual use.

To address this, in addition to the initiatives mentioned in the last section to increase training of the lay public, a number of EMS services have compiled registers of public access defibrillators in their community and are using mobile apps such as PulsePoint (USA), GoodSAM (UK and Australia), HeartRunner (Sweden, Denmark) and MyResponder (Singapore) to enrol those willing and able to respond to an emergency. When the EMS dispatcher receives a cardiac arrest call, they can activate the nearest first responders through the mobile app and give the location of the nearest AED.

In an impact evaluation of GoodSAM in Victoria, Australia, when GoodSAM responders arrived first they were on average nearly 2 minutes faster than dispatched paramedics – a significant time saving when early intervention is crucial. Survival in this group was 41% compared with 11% for those cases that GoodSAM responders did not attend. In Singapore there are now more than 70,000 responders and 20,000 AEDs registered in their system for a population of under 6 million. There, and in other cities where most of the population live in high-rise buildings, use of AEDs by janitors or security personnel has also proved effective.

The role of the first responder is also of course to provide early CPR – either to assist the bystander or initiate it. To improve and monitor the quality of this CPR, Singapore EMS have now provided the Laerdal CPR card to their first responders. The card gives real-time feedback to the rescuer on the quality of CPR. The latest version also includes Bluetooth. This can give improved feedback to the user on their mobile phone, but importantly it can also transmit through the phone the user performance in real time to the dispatcher to enable them to give verbal feedback where needed. It also facilitates post-event review and quality assurance of the system.

Dispatcher sees registered AEDs in the vicinity of the emergency.

Video-based communication between bystander and dispatcher.

Luqman’s Story

Muhammad Luqman Abdul Rahman of Singapore is only 18 years old and has already helped save nearly 20 lives. He was just 13 when he made his first save: on the way home from school his My Responder app from the Singapore Civil Defence Force alerted him that a factory worker had suffered a heart attack and collapsed close by. Having sprinted to the scene, Luqman performed CPR until the ambulance arrived – and later recalled that he had felt daunted because “actual doing was very, very different from practising.”

At first, Luqman’s parents were against his responding, fearing that the boy would be blamed if something went wrong. Asking them to come along the next time the alert sounded, he won them over – and by now they must be the proudest parents in Singapore.

High Performance EMS CPR

The quality of CPR delivered by the responding emergency team is also a very important predictor of survival. Such “High performance EMS CPR” is sometimes called the “dance of resuscitation”, “the CPR ballet”, or “pitstop approach”. Like professional racing car pit crews, each team member should know exactly what to do with minimal waste of time and effort. The Resuscitation Academy in Seattle, USA, recommends that Quality Improvement (QI) programs should provide performance feedback to involved personnel after every cardiac arrest.

Digital downloads from CPR aids and defibrillators quantifying CPR performance now allow for such feedback on chest compression rate and in some cases compression depth, incomplete release, and time without compressions before and after a shock and when performing the advanced manoeuvres of intubation and IV access. Laerdal and the American Heart Association (AHA) are working with the Resuscitation Academy to develop a Resuscitation Quality Improvement program, RQI for EMS, based around the principle of Low-Dose High- Frequency Training which has been validated in hospitals. This program will enable EMS personnel to refresh their CPR skills in short but frequent sessions on simulators positioned in their base station. An analytics program will help these skills to be tracked, and the TeamReporter app will help improve team performance.

Tim’s Story

Tim Hillier is Deputy Chief, Professional Standards at Medavie Health Services West, Saskatoon, Canada.

With 200 firefighters, primary care paramedics and EMTs, Tim and his team have fully embraced the need for high-quality CPR and real-time feedback.

“The way I look at it, I know that there are six more people alive in Saskatoon each year that wouldn’t have been if we hadn’t done this.”

Tim Hillier

TeamReporter and other QCPR aids

To enable EMS and other healthcare professionals to practise High Performance CPR with their colleagues at a time of their choosing either in a classroom or in their workplace, Laerdal is developing the TeamReporter app. All they will need is a Laerdal QCPR manikin to record the compression and ventilation data and a mobile phone to video the session.

At the end of the session the manikin data and video are uploaded to the Cloud for analysis. The team will then get detailed stats and a summary video of their performance for debriefing. Comparison of the stats with other peer groups adds a competitive element that has proved very popular with users and encouraged them to improve performance.

The CPRmeter is a high-intensity and re-usable system for professional health workers. The CPRcard is a personal device, to be carried around at all times, giving CPR performance guidance to the rescuer.

EMS Best Practice Going Global

Following the success of the Resuscitation Academy started in King County, Seattle in 2008, a meeting of EMS international experts was held in 2015 in Utstein Abbey, near Stavanger, Norway, to address the challenge of spreading EMS best practice around the world. This led to the establishment a year later of the Global Resuscitation Alliance (GRA) charged with increasing survival from cardiac arrest by 50%. The GRA has since held workshops in Korea, Japan, Singapore, China, Australia, Norway, Sweden, Denmark, Switzerland, the UK and, to address the challenges in LMICs, in India.

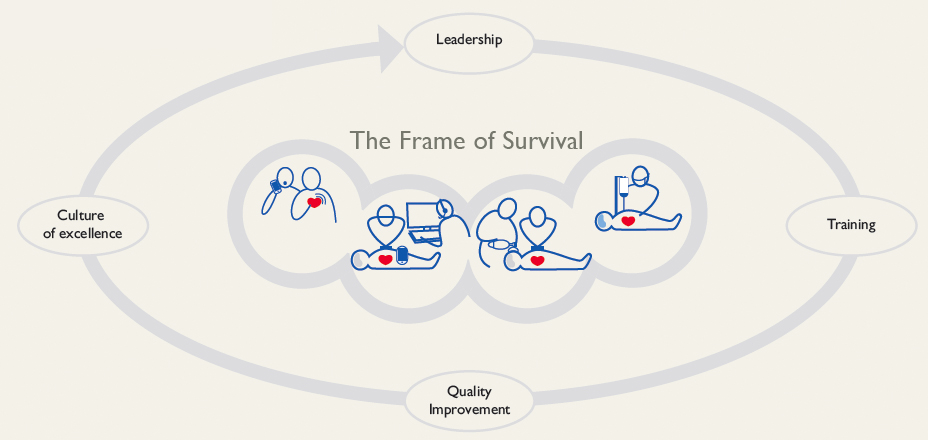

Although the approach taken by the GRA is centred around the well-established Chain of Survival, it is now evident that to maximise the impact of the links in the Chain they need to be embedded in a framework of strong leadership, systematic refresher training, and a quality improvement system that drives a culture of excellence. This is now being referred to as the Frame of Survival and underpins the GRA approach enumerated in its 10 steps to improve survival.

There are now 76 case studies on the GRA website covering these ten steps. Several of them have already been mentioned on this page regarding community CPR training, telephone CPR, first responder AED programs, and ensuring High Performance CPR by EMS personnel.

All this said, the first step to improving survival is data collection i.e. Establishing a Cardiac Registry – knowing how well the system is doing and monitoring progress is fundamental. Measure to Improve should be the mantra of all systems. There are 13 GRA case studies relating to data collection, one of which details impressive increases in survival across several systems which have had such registries for many years.

Best Practice

to Improve Cardiac Arrest Survival

- Cardiac Arrest Registry

- Telephone CPR for Consistently Improved CPR

- High Performance EMS CPR

- Rapid Dispatch

- CPR Performance Data

- First Responder AED Programs

- Smart Technologies to Expand CPR and Public Access Defibrillation

- CPR/AED Training in Schools and the Community

- Accountability

- Work towards a culture of excellence

Mickey Eisenberg – EMS pioneer

A Beacon for All

Mickey Eisenberg has been, and remains, an untiring pioneer in lifesaving of worldwide importance. Under his leadership King County, Seattle has been a beacon for everyone with survival rates for witnessed cases with a shockable rhythm – the Utstein benchmark – exceeding 50%.

The research conducted with his colleagues in the Center for Evaluation of Emergency Medical Services has been crucial for identifying what works best and has been the basis for many updates of international guidelines. The basic principles are set out in his book “Resuscitate! How Your Community Can Improve Survival from Sudden Cardiac Arrest” and are being spread to communities across the world through the GRA.

Mickey strongly believes the success is down to collaboration, expressing his appreciation to professionals who helped make Seattle a world leader: “the hundreds of emergency dispatchers, the thousands of EMTs, and the hundreds of paramedics.” In his book, he draws up the prerequisites for developing a culture expressed in the Frame of Survival.

The graph compares trends in survival from community cardiac arrest expressed in number of survivors per million population from 2001 through to 2018 in several countries with the results from Seattle. It shows that substantial increases in survival can be achieved by following the best practices of the GRA of which EMS systems in these countries are members. The results from Denmark are particularly noteworthy and have been described earlier on this page.

A Devastating Duo

Stroke

According to the Global Burden of Disease statistics, there were 5.5 million deaths from stroke in 2016, 39% in the under 70s. There are over 13.7 million new strokes each year and 80 million people currently living who have experienced a stroke. And over 116 million years of healthy life are lost each year due to stroke-related death and disabilities: 63% in those under the age of 70. So, stroke does not just strike the elderly – a common misconception. Approximately 2 million brain neurons are damaged for each minute that it is left untreated. This does not sound a lot bearing in mind that we each have about 100 billion neurons in our brains. But if those damaged are in critical areas of the brain, even a small injury can be devastating.

Sepsis

Sepsis is an overcharged response of the body to infection which injures its own tissues and organs. Recent data from the Global Burden of Disease study published in the Lancet indicate that it affected almost 50m people worldwide in 2017 with 11m sepsisrelated deaths. This is more than double previous estimates, with babies and small children in poorer countries at greatest risk. The leap in deaths comes from an attempt to quantify what is happening in LMICs from where data were previously underrepresented: the Lancet study is the first to produce global estimates across 195 countries.

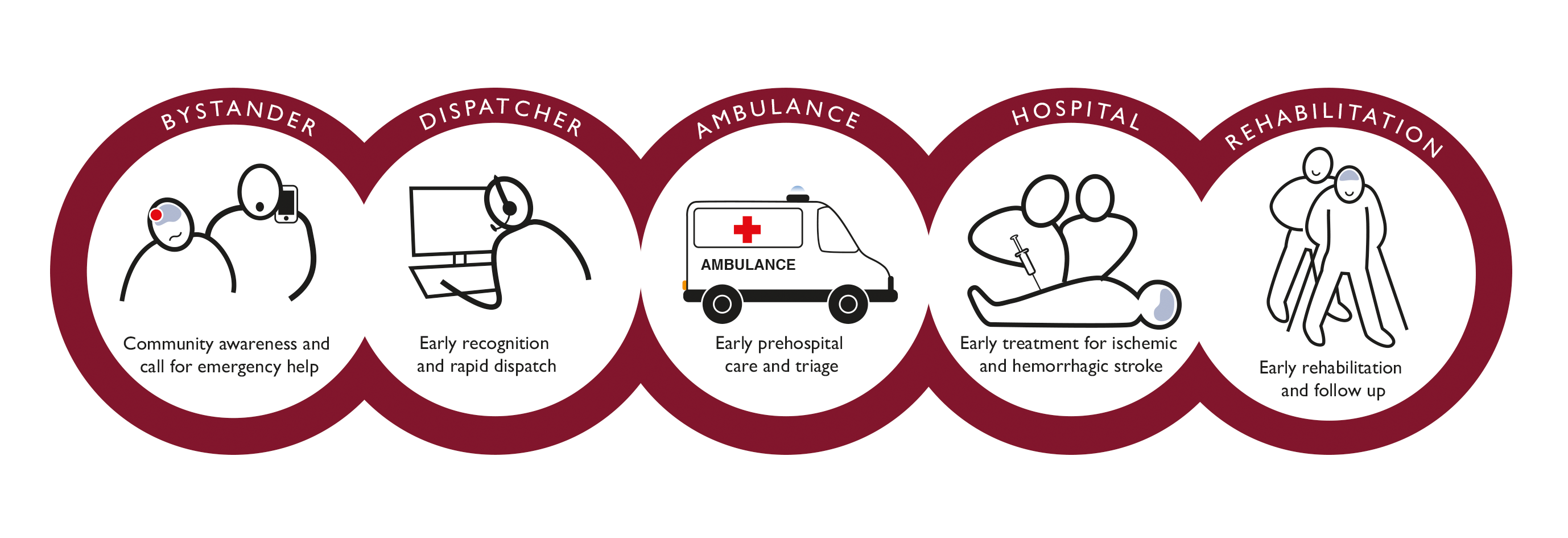

Stroke and sepsis share an initial and the same number of letters, and they devastate the lives of millions, but that is not all they have in common. For both stroke and sepsis, time is of the essence. Early recognition with the help of an emergency dispatcher, a welltrained ambulance crew, rapid transport to a properly resourced centre, and early intervention by a well-trained hospital team are critical for both survival and quality of life. This is illustrated in the stroke equivalent of the cardiac arrest Chain of Survival, established at an Utstein meeting in 2018.

Public campaigns have been widely employed to improve the recognition of the symptoms of a stroke and sepsis, but more can be done. For example, live-video streaming from the home to the emergency dispatcher coupled with improved training and Artificial Intelligence could help in rapid diagnosis. If there are serious delays in recognition, then subsequent attempts by healthcare personnel to save the patient from death or serious disability may be futile. This said, though, a very rapid response when the patient arrives at the hospital is essential.

In the case of stroke, it is essential to determine whether it is caused by a clot or bleeding in the brain before medical treatment begins. If a clot is present it needs to be dissolved quickly with a drug (trombolysis), but if bleeding is occuring such a drug will make matters worse. A brain scan is essential to differentiate between the two, and a well-drilled team involving emergency physicians, radiologists and surgeons is the key to successful treatment.

The measure of the quality of treatment in such cases is what is called “door to needle time (DNT)”: the period from when the patient enters the hospital to when they receive thrombolysis. The AHA/American Stroke Association guideline – typical of global standards – is that the average DNT should be under 60 minutes. High-fidelity simulation can prepare the team to deal with the emergency and help reduce this time as described on the page “Quality Care in Hospital“.

Delay of call and EMS recognition of emergency

| Incidences | % deaths | Deaths | Typical delay to call EMS* | Typical accuracy of dispatcher recognition* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sudden cardiac arrest | 5m | 98% | 5m | 1min | 75-85% |

| Stroke | 15m | 33% | 5m | 30min | 60-65% |

| Sepsis | 50m | 22% | 11m | 30min | 50-60% |

| Accident | 100m | 5% | 5m | 1min | 98% |

* These estimates are for HICs. The situation is very much worse in LMICs

Training in teams for faster diagnosis and more efficient treatment of sepsis and stroke.

The World Health Organization Comes to Utstein

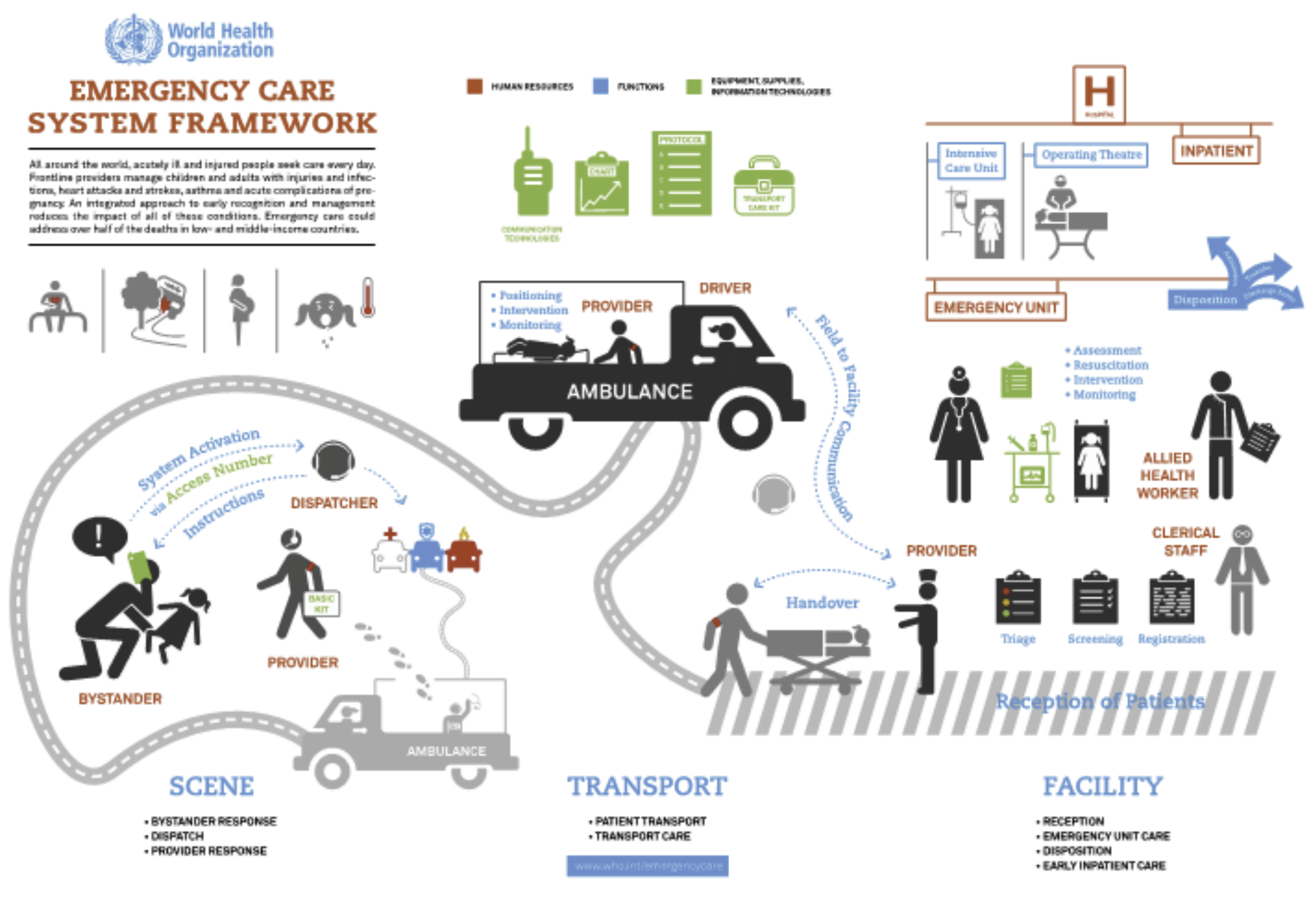

The World Health Organization (WHO) has defined a series of essential functions for an Emergency Care System that spans from pre-hospital care – including the role of the bystander and the dispatcher – and transport through facility-based emergency unit care to early operative and critical care.

In the 2018 World Bank Monograph, Disease Control Priorities: Improving Health and Reducing Poverty, Teri Reynolds, head of the Emergency, Trauma and Acute Care program at the WHO, along with co-authors set out key policy strategies for strengthening national healthcare systems globally to provide emergency care more effectively. Although most of the evidence for system improvements comes from HICs, the authors concluded that “such improvements can also be made – affordably, sustainably, and with dramatic impact – in LMICs”. As one of the follow-ups to this report, the Laerdal Foundation and the WHO, represented by Teri and her team, are organising an expert meeting on Strengthening Emergency Care Systems at Utstein Abbey outside Stavanger, Norway. This historic site has hosted more than 25 expert meetings supported by the Laerdal Foundation which have led to landmark recommendations for evaluation and reporting on various aspects of emergency medicine and education.

Utstein Abbey

Teri Reynolds

Scientist, World Health Organization

Emergency Care for 10 SDG Targets

3.1 Maternal mortality: treatment of obstetric emergencies, including pregnancy related bleeding.

3.2 Under-five mortality: treatment of acute diarrhoea and pneumonia, the top killers of children.

3.3 Deaths from malaria and other diseases: treatment of acute infections and sepsis.

3.4 Reduce mortality from NCDs: treatment of heart attacks, strokes, and other acute exacerbations of NCDs.

3.5 Strengthen treatment of substance abuse: treatment of overdose and other complications.

3.6 Halve road traffic deaths and serious injuries by 2020: post-crash emergency care.

3.8 Achieve Universal Healthcare Coverage: emergency care is an essential component.

3.9 Deaths and illnesses from hazardous chemicals: treatment of acute exposures.

11.5 Deaths caused by disasters: preparedness and response to save lives and mitigate system collapse.

16.1 Violence-related deaths: treatment for victims of violence.